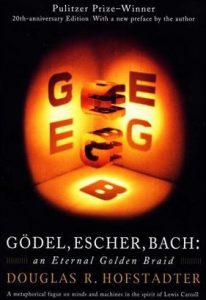

Never mind the Escher and Bach stuff; that’s just window dressing. This book is about Godel’s Theorem. And wow, what a book.

Imagine a glorious future in which, by means of magic and genetic engineering, the human species is transformed into a better, smarter, faster, more beautiful, more creative, more moral, stronger, happier species, a more alive species. We make Elysium, then we live in the Elysium we’ve created.

In this Arcadia, this Heaven, this Eden, this Platonic Form of the world animated and electrified by benevolent intelligence, you walk across grassy fields and you see the whole thing, The Dream:

Everyone is wearing flowing white robes. (Why? Just because.)

Over there athletic people engage in athletic contests, their good-natured competition embodying grace, fluidity, and the confidence of a well-disciplined, healthy body.

Over here, mathematicians use sticks to draw in the dirt on a river bank, proving astoundingly beautiful and useful new theorems.

In another direction a young man or woman lounges, back against a tree, releasing sweet strains of melody into the air by means of some sort of elegant string instrument.

Are you with me?

Okay.

In that universe, every non-fiction book is this good.

What’s it about?

It’s about, principally, Godel’s Theorem. The other stuff, at least in the first part (Escher, Bach, etc.), is just add-ons. Godel’s Theorem is often mis-characterized as “disproving all of mathematics!” or some similar nonsense. No. It says something about formal mathematical systems, systems of clearly stated axioms with clearly stated rules of inference for deriving implications of the axioms. The theorem essentially says that any formal system sophisticated enough to be used for number theory – reasoning about integers – either has internal inconsistencies or is unable to prove every truth in number theory.

This does not “Undercut all of mathematics” or whatever. It simply means that a consistent formalistic approach to mathematics can never derive all mathematical truths. There are some truths that can only be proven in other ways. Indeed, Godel shows how to prove some of those truths by reasoning outside formal systems!

To prove it, Godel had the profound insight that any formal system can be re-interpreted as a set of numbers and arithmetical operations on them, so formal number theory talks about itself! This is so cool.

E.g., suppose your formal system has the symbol string x#@^&?G-!y. (This might mean, say, “x is the largest number in the prime factorization of y.”) We also have a rule that allows us to derive x<=y (x is not greater than y) from the first string. But we also can interpret x as 5, # as 0, @ as 2, and so on, so the initial symbol string can be interpreted as a number. And so the second string is a number that we can derive from the first. So the rules of inference in this interpretation are arithmetic operations on numbers. Thus we can apply mathematical reasoning to the system and derive conclusions about the symbol strings it will generate and those that it won’t generate.

A simplified analogy: Suppose that we can prove – by reasoning outside the formal system – that the system will never produce a string whose number is prime. What Godel proved, in this analogy, was there is always a symbol string that asserts “N is a prime number” (in the first interpretation) whose number was N (in the second interpretation). Thus, if the statement is true, the formal system will never prove it!

(It is possible to verify that a well-designed system will never “prove” a false statement, so you can avoid that problem.)

In fact, no only do such true-but-formally-unprovable statements exist, in any formal system complex enough to be useful, but an infinity of them exists!

It was the idea of reinterpreting the symbols as numbers that was Godel’s real stroke of freakin’ genius. The theorem is based on that.

Anyway: The next time someone tells you, “Godel’s Theorem proves that all mathematics is invalid,” or whatever, just give them a wedgie and move on. All it proves is that a certain approach to mathematics cannot prove everything. Which, unless you had unrealistic ambitions for it in the first place, is not that surprising.