Here’s some text. Dude!

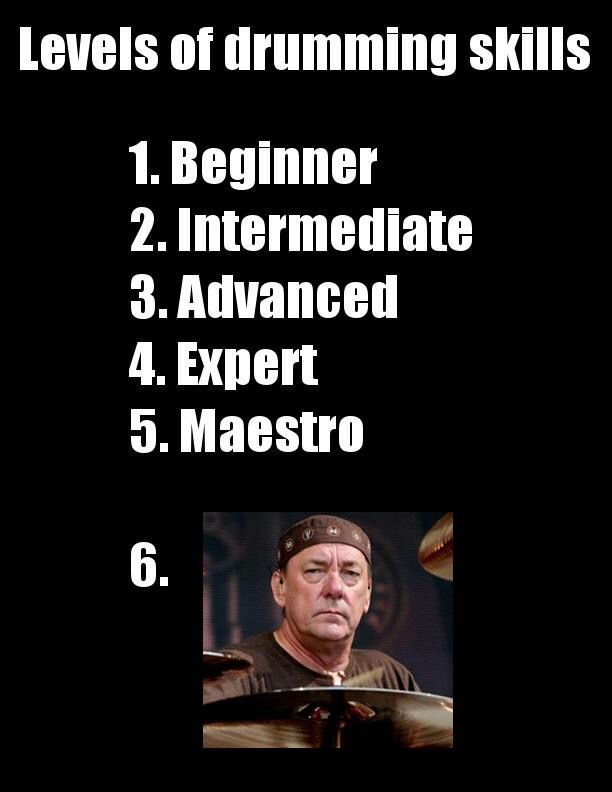

Neil Peart, 1952 – 2020: An Appreciation

I just heard the sad news that Neil Peart, the drummer for Rush, died on January 7. Rest in peace, Neil.

Excuse me while I go all fanboy for the rest of this essay.

You will hear a lot of people saying, correctly, that he was the best rock drummer of all time.

Yes. But why was he? I want to break this down for non-drummers and non-musicians generally, starting with the simpler stuff and working up to the high-level musicianship.

• His speed and ability to get around the toms were top shelf. That is, he could move from one drum to another seamlessly.

• His rhythm was incredibly precise. No one else in rock had the metronome-like precision that Peart had. Rush is a classic example of a “tight” band, one that plays with rhythmic precision and with all instruments exactly in synch with each other.

• He was excellent with non-standard time signatures. Maybe – maybe – there are other musicians in western music right now who are as comfortable in seven time as Peart, but no one was more comfortable, more at home, in that unusual rhythmic structure. And consider the insane syncopation of the 13/8 section of Jacob’s Ladder (starts around 4:53) or that blazingly fast 7/8 time solo section in Marathon (starts at 2:55 and gets really crazy at 3:43). When that album, Power Windows, came out, a reviewer for Rolling Stone spoke of Peart “subdividing the beat into syncopated algebra.”

• The ability to switch between straight-ahead feel and triplet-based feel – this is much harder than it seems when you’re not practiced at it. For an obvious example cue up their shamefully underrated song Available Light from Presto. As the last run-through of the chorus is starting, Peart plays a powerful triplet-based fill over Geddy Lee’s vocal. (At around 4:10, but start listening at 3:55 so you have musical context.) If you’re not a musician it might almost sound like Peart has messed up. Heh, no. What happens is that while the music stays in 4/4 time, each of those four beats can themselves be divided into four beats or into 3 beats. Peart here is switching from the straight-ahead 16-beats-per-measure feel to a triplet-based 12-beats-per-measure feel. Few rock drummers can do that as fluidly, and no one can do it more fluidly.

• He knew his instrumentation, i.e. how to use all elements of a drum set. Some non-standard ones too: on Moving Pictures he used plywood in at least one song. “More cowbell” is a joke now, but Peart knew when to use it. Try Witch Hunt starting around 1:36 here. He taught us (at least he taught me) how to use china-type cymbals, which I at first tried to use like crash cymbals, to distasteful effect. Uh, no. You use them like a high-hat, to mark time. Try Subdivisions starting at 4:50. (Peart isn’t only marking time here, of course; other stuff is going on too.)

• Peart actually listened to the other instruments and played with them, so they sounded like a band and not a bunch of guys who happened to be playing music in the same room. (I’m looking at you, Ringo Starr.) In the last paragraph I mentioned marking time, but a good drummer rarely just marks time while doing nothing else. Doing something else requires listening to the other instruments so your something else is musically connected to what the other instruments are doing at any moment.

• Limb independence. Common question from non-drummers: “How do you play four different things with your four different limbs?” It can’t be explained in words; you have to just feel it. Usually you put two or three limbs on autopilot, and you’re actually thinking about what you’re doing only with the remaining one or two. A good Peart example: The Big Money, starting at 2:08 where he’s doing something… advanced… with the high-hat cymbal while keeping everything else going. (The high-hat is the two cymbals that can be clamped together; you use your left foot to close them together or separate them. Unfortunately it’s hard to hear the high-hat on YouTube.) My reaction on hearing that for the first time was “How the hell is he doing that!?”

• He was so creative. He played fills that I wouldn’t have thought possible if I hadn’t heard him playing them. An excellent example is the classic set of fills in Tom Sawyer, starting at 2:33, those canonical MUST AIR DRUM TO THIS! fills. If you know a drummer, play this song and see if s/he can resist air drumming to those fills. Answer: No.

I don’t always listen to Tom Sawyer, but when I do, so do my neighbors.

And the way he played with rhythm! Yes, he was a supremely intellectual drummer – he always thought about what he was doing – yet there’s unmistakable playfulness in the way he dove in, experimenting, and changed things up to throw you off, just when you thought you knew what he was going to do next.

• But the big thing you noticed but couldn’t articulate, if you aren’t a musician, was his phrasing.

Whut?

His phrasing is the main thing that made you say, “There’s something about his drumming that’s just so damn cool, but I can’t explain it.”

Phrasing means a couple of things; here I’m referring to when an instrumentalist sets up structure on a small time scale. It’s almost creating little sentences or clauses in the music. If composition is structure on a large time scale – over the course of an entire piece of music – phrasing is playing with structure on the time scale of a couple of bars (measures) of music.

For example, the compositional structure of Tom Sawyer is that they open with that slammin’ drum beat over a growling synthesizer, run through a couple of verses, move into a screaming guitar solo, then pound through to the end.

Phrasing is the way that Peart would play fills within a verse or just within a few measures. For example, he establishes a basic beat in the first few measures, then plays with variations on it for the rest of the song.

Or consider Limelight, in which he slyly plays a four-beat across the bass and guitar’s three-beat starting at 3:14.

Often, in the first run-through of a verse in a Rush song, Peart would play a fill in a certain way (and because it was Peart, it would be a good fill). On the second verse, he’d usually play it a little differently. He’d omit a drum hit, for instance, so there’d be a gap where you expected to hear something. Or he’d stop the fill short of where you expected it to end, or extend it a couple of beats longer. It’s hard to capture in words the sheer energy and intellect in his drumming.

Like all musicians with good phrasing, Peart would set up an expectation in your mind, then sometimes satisfy it and sometimes violate it. He’d establish a theme, then play with it.

By the way, this is an example of what musicians mean when they say “variations on a theme,” but they almost never use this phrase in the context of drumming. That’s because most drummers aren’t Neil Peart, so they don’t even rise to the level where “variations on a theme” is relevant in their drumming.

No other drummer in rock music has come within a light-year of Neil Peart’s phrasing. It’s retarded. He doesn’t even have any competition. Not in rock.

There are some jazz drummers with kick-ass phrasing, but that’s a different musical universe from rock.

And that is why Neil Peart was, and is, and probably always will be, the best drummer in the history of rock and roll.

Thank you, Neil, for setting the bar so high for the rest of us. Actually, you’re kind of a bastard about that. Did you have to set the bar so damn high? Well, we might not be able to rise to the standard you set, but it’s a pleasure to try, and trying has made us all immeasurably better drummers.

The 2019 Self-Published Fantasy Blog-Off

The Self-Published Fantasy Blog-Off is a contest that writer Mark Lawrence does every year. This year is the fifth year, and it is underway right now. I entered The War of the First Day during the entry period in June and then became occupied with other things.

I had assumed there would be no whisper of progress until WHAM! the drop-dead date hit, and then all decisions would be revealed at once.

I just learned the reviewers are posting results, decisions, impressions, and reviews as they go.

Oh, man, this is torture! Now I have to decide if I want to obsessively check the Twitter feed, the Facebook page, the update page at Mark Lawrence’s web site, etc., all the time. Every week? Every day? I tell myself, “Don’t do that to yourself, Tom,” but the temptation is there.

Maybe not check at all? I am actually pretty busy with my day job, which has meant so far that I tend to forget about the blog-off for days or even weeks at a time. But now that I know that updates are coming along in real time…

People who have reviewed my novel have reviewed it very kindly. (Though one didn’t like the cover, which indeed may give the false impression that it’s erotica. Whoops.) But the competition! Three hundred novels!

Gaaaaah!

AIs for Change!

Back in May, Artificial Intelligence expert Janelle Shane pulled down thousands of petitions from Change.org and used them to train an artificial neural net so it could generate petitions of its own. Here’s a sample of what it came up with:

• Dogs are not a thing!! Dog Owners are NOT Human beings!!

• Help Bring Climate Change to the Philippines!

• Filipinos: We want your help stopping the killing of dolphins in Brazil in 1970’s

• Mr.person: I want a fresh puppy in my home

• Rooster Teeth: Have Rooster Teeth Fix Your Responses To Obama

• Donald Trump: Change the name of the National Anthem to be called the “Fiery Gator”

• The people of the world: Change the name of the planet to the Planet of the Giants

• Dr James Alexander: Make the Power of the Mongoose a Part of the School’s Curriculum

Via slatestarcodex.com/2019/06/26/links-6-19/

Another Encouraging Result

Just got this from the Al Blanchard contest:

Hi, Thomas,

On the behalf of the Al Blanchard Award Committee, I’m pleased to let you know that your story, “The Great Auk Caper,” made it to the first round of the contest in that it was among the top ten picks of one judge. Congratulations! Although you didn’t win, this is no mean feat, given that we received around 140 submissions. We hope you’ll try the contest next year.

In the meantime, good luck with your writing!

Sweet. If this sounds familiar, it’s because this contest lets you enter a story twice and I posted about the earlier entry, which also did well, in July 2017.

Joseph Campbell and Popular Fiction

A lot of popular fiction starts out with a boring, pedestrian scene, e.g., we see our hero or heroine coming home and saying, “Thanks for cooking X, honey!” X was Y’s favorite dinner, we’re told. Actually we don’t need to know what they’re having for dinner or the main character’s favorite dinner. Just plunge right into the conflict.

I suspect this sort of thing in modern fiction is due to a misunderstanding of Joseph Campbell. In his Hero With a Thousand Faces, Campbell noted that many myths from around the world have an ordinary person yanked out of his comfortable pedestrian life and thrown into a world of savage magic, challenges, and adventure. This has led many modern authors who don’t understand the difference between myth and popular fiction to think that their stories should be set up this way. Whoops, no. This is fiction, not myth. Stories should plunge right into the conflict. Don’t show us the character going about his/her normal life before things get interesting. Make them interesting from the first sentence. If we need to know certain features of the main character’s day job or whatever, then tell that as backstory later, dropping in details as we need to know them.

Works of popular fiction that dwell on the normal situation before the conflict really gets going, without boring the reader, are rare. The only two I can think of are Gone With the Wind and The Hobbit. And in Gone With the Wind it works because we’re told on the first page that this is Georgia in April 1861, so we know our characters are on the very brink of a terrible civil war. In The Hobbit it works because the first sentence introduces us to a mystery: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” Since no one knew what a hobbit was when the book was first published, we get a mystery that piques our curiosity right from the first sentence. And as we read on we realize the fictional environment we’ve been thrown into is thoroughly new and exotic.

Furthermore, to return to Campbell, the old myths Campbell was discussing actually don’t spend much time detailing the hero’s pedestrian life before things get kinetic. They just say, as it were, “One day Joe, a humble shepherd, encountered a witch and…” etc. Total expenditure on Joe’s initial life situation: three words, “a humble shepherd.” And the “humble” is optional and the “a” doesn’t really count. For example, in Hero’s Chapter 1, “Departure,” Campbell considers the story of

an Arapaho girl of the North American plains. She spied a porcupine near cottonwood tree. She tried to hit the animal, but it ran behind the tree and began to climb. The girl started after it…

And of course an adventure ensues. Notice there’s no breath wasted on detailing the girl’s normal life before she chases the porcupine into the sky. She’s just a girl walking in the woods, and… We’re off!

So any writers who dwell at length on the main character’s normal life at first, really aren’t modeling their story after myth very closely anyway.

I am not blaming Campbell for this mistake that some writers make; I’m blaming a misunderstanding of Campbell. Myths and popular fiction are very different things!

Review of Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher, Bach

Never mind the Escher and Bach stuff; that’s just window dressing. This book is about Godel’s Theorem. And wow, what a book.

Imagine a glorious future in which, by means of magic and genetic engineering, the human species is transformed into a better, smarter, faster, more beautiful, more creative, more moral, stronger, happier species, a more alive species. We make Elysium, then we live in the Elysium we’ve created.

In this Arcadia, this Heaven, this Eden, this Platonic Form of the world animated and electrified by benevolent intelligence, you walk across grassy fields and you see the whole thing, The Dream:

Everyone is wearing flowing white robes. (Why? Just because.)

Over there athletic people engage in athletic contests, their good-natured competition embodying grace, fluidity, and the confidence of a well-disciplined, healthy body.

Over here, mathematicians use sticks to draw in the dirt on a river bank, proving astoundingly beautiful and useful new theorems.

In another direction a young man or woman lounges, back against a tree, releasing sweet strains of melody into the air by means of some sort of elegant string instrument.

Are you with me?

Okay.

In that universe, every non-fiction book is this good.

What’s it about?

It’s about, principally, Godel’s Theorem. The other stuff, at least in the first part (Escher, Bach, etc.), is just add-ons. Godel’s Theorem is often mis-characterized as “disproving all of mathematics!” or some similar nonsense. No. It says something about formal mathematical systems, systems of clearly stated axioms with clearly stated rules of inference for deriving implications of the axioms. The theorem essentially says that any formal system sophisticated enough to be used for number theory – reasoning about integers – either has internal inconsistencies or is unable to prove every truth in number theory.

This does not “Undercut all of mathematics” or whatever. It simply means that a consistent formalistic approach to mathematics can never derive all mathematical truths. There are some truths that can only be proven in other ways. Indeed, Godel shows how to prove some of those truths by reasoning outside formal systems!

To prove it, Godel had the profound insight that any formal system can be re-interpreted as a set of numbers and arithmetical operations on them, so formal number theory talks about itself! This is so cool.

E.g., suppose your formal system has the symbol string x#@^&?G-!y. (This might mean, say, “x is the largest number in the prime factorization of y.”) We also have a rule that allows us to derive x<=y (x is not greater than y) from the first string. But we also can interpret x as 5, # as 0, @ as 2, and so on, so the initial symbol string can be interpreted as a number. And so the second string is a number that we can derive from the first. So the rules of inference in this interpretation are arithmetic operations on numbers. Thus we can apply mathematical reasoning to the system and derive conclusions about the symbol strings it will generate and those that it won’t generate.

A simplified analogy: Suppose that we can prove – by reasoning outside the formal system – that the system will never produce a string whose number is prime. What Godel proved, in this analogy, was there is always a symbol string that asserts “N is a prime number” (in the first interpretation) whose number was N (in the second interpretation). Thus, if the statement is true, the formal system will never prove it!

(It is possible to verify that a well-designed system will never “prove” a false statement, so you can avoid that problem.)

In fact, no only do such true-but-formally-unprovable statements exist, in any formal system complex enough to be useful, but an infinity of them exists!

It was the idea of reinterpreting the symbols as numbers that was Godel’s real stroke of freakin’ genius. The theorem is based on that.

Anyway: The next time someone tells you, “Godel’s Theorem proves that all mathematics is invalid,” or whatever, just give them a wedgie and move on. All it proves is that a certain approach to mathematics cannot prove everything. Which, unless you had unrealistic ambitions for it in the first place, is not that surprising.

Avengers: End Game

SPOILER WARNING!

A year ago, almost to the day, I offered a conjecture about how the Infinity War story would be resolved. I didn’t call it. But I must have been in the writers’ heads to an extent, because the call I made was used as a fake-out in End Game.

Last year I wrote,

One possibility is that the entire first movie actually takes place in what is, from our point of view, an alternate timeline.

Dr. Strange, to save half the sentient beings of the universe from being genocided by Thanos, had to go way back into the past and engineer a different universe from the one he was in.

That universe is the one we we think of as the real universe.

As it turns out, this isn’t how End Game is resolved. But just before the last battle of the movie, Thanos says to the good guys (I’m working from memory here),

“Before, when I killed half of all sentient beings, it wasn’t personal. But you’ve angered me so much that I’m going to kill everyone. I’m going to reduce the universe to subatomic ash, then re-build it from scratch with new, better beings.”

“They’ll be born in blood,” someone says, to which Thanos replies, “They’ll never know.”

At those lines of dialogue I was like, “Wow, I was right!”

Well, no. I didn’t call their ending, but I called their fake-out, so yeah!

Great flick, by the way. Go see it, if you’ve seen enough of the other Marvel movies to have good context. And if you haven’t, watch all the Iron Man movies, Captain America movies, and Avengers movies, then watch this one.

In a pinch, you can just watch Captain America: Winter Soldier, Captain America: Civil War, Avengers, Avengers: Age of Ultron, and Avengers: Infinity War first.

The Mediæval Bæbes’ Christmas carol album, Of Kings and Angels

Just listened to this over Christmas. Overall it’s a good album. The liner notes contain the lyrics, with translations where appropriate, and notes on the carols. My listening notes:

1. I Saw Three Ships. Good.

2. We Three Kings. Good.

3. The Holly and the Ivy. Good. Note this is a different performance from the one on their album Mistletoe and Wine.

4. Ther Is No Rose of Swych Vertu. Meh at best. They should do it more up-tempo.

5. Ding Dong Merrily on High. Good.

6. The Angel Gabriel. Beautiful.

7. In the Bleak Midwinter. Good.

8. Good King Wenceslas. Ugh, unlistenable. They do stupid, pointless things with the melody, including either quarter-tones or a very bad lead singer. I didn’t finish listening to it. Regarding the quarter-tones, if that’s what they’re supposed to be, this carol was written by some English dude in the 1800s, and plainly this album is intended for an Anglospheric audience. This is the western musical tradition; stick with half-tones, puh-leaze!

9. Gaudete. The version on this album is awesome! Some delightful surprises. I could say more, but…I don’t want to ruin the surprises!

10. Once in a Royal David’s City. Good.

11. Veni Veni Emmanuel. Very nice.

12. Away in a Manger. Good.

13. In Dulci Jublio. Good. Note this is a different version from the one on Mistletoe and Wine. By the way, the lyrics are a macaronic combination of English and Latin. “Macaronic” in this context doesn’t refer to pasta; it refers to a combination of languages. A Net search reveals that the earliest known version of the lyrics – which are around 700 years old! – are a macaronic combination of German and Latin. A guy named Pearsall translated them into macaronic English and Latin in the 19th century. If the melody sounds familiar, that’s because it’s also been more loosely translated into the carol “Good Christian Men Rejoice.”

14. The Coventry Carol. This is a horrifying “carol” about King Herod slaughtering all the male infants. Yikes! I didn’t listen to it. Why would you put that on a Christmas album!?

15. God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen. No! See comments on Good King Wenceslas.

16. Silent Night. Good.

17. Corpus Christi Carol. The lyrics are kind of a downer, and the singing is too physically piercing.

Evening’s Empire

Evening’s Empire by Craig Kosloksky is a non-fiction book about “mankind’s colonization of the night” by various lighting technologies. Via a review, a snippet from the book:

“…the power of midnight, solitary and profound, to strip away the vanity of the day.”

I like that; it captures well why things seem so different at night. The literal noise of the daytime world, not to mention the social cacophony, prevent (or certainly discourage) one from thinking about profound matters. Also, the daytime world has the frenetic pace of a competitive species that is mortal and subject to aging. Things must be done fastfastfast! Night has an entirely different pace, no pace at all, really. In the dark and quiet, profound thoughts set their own pace, and their own pace is slower, much more measured. The darkness removes the distraction entailed in observing things around you. It lets you retreat into yourself, into your own thoughts.

Quotidian things distract us from profound things. If there is a devil, he is a creature of the day, not of the night.